Adoption Awareness Month

What a joy and privilege to talk about adoption with FIT4MOM Madison as part of Adoption Awareness Month. For those of you who do not know me, my name is Stacey Roy; adopted from South Korea, raised in Louisville, Kentucky, and I’ve called Madison home for the past 15 years. I have three children, ages ten to four. Speech-language pathologist, coffee lover, foodie.

Adoption has been a part of my life, literally, since infancy and its significance and impact on my life has evolved and shifted through the years. Many years ago, my parents and a whole slew of extended family drove to Chicago O’Hare, where a petite, six month old preemie baby was the first one off the plane and placed in my mother’s arms. (Homecomings now are quite different, as many adoptive families spend days, sometimes weeks, in an adoptee’s hometown or country before they are able to come home. More on that later.)

I am the youngest of two; my sister is also adopted from South Korea, but we are not biologically related. Growing up, adoption was naturally woven into our family dynamic. I was raised by Caucasian parents in a predominantly white community. I grew up with some African American/Black friends and also had family friends with adoptees from Korea and Guatemala, but we were all definitely the minority in our neighborhood and school. Even though some friends growing up would comment on how I looked like my dad or acted like my mom, it was very obvious I was not my parents’ biological child. That realization really hit when we had the genetics unit in elementary school and I could not say where I got my dark brown eyes from or thick, coarse black hair. Throughout my childhood, I feel like my parents saw the need to provide opportunities for my sister and I to embrace our differences without any shame, inferiority, or naivety that we live in a world that doesn’t see color.

For as long as I can remember, our adoptions were celebrated. Not in an outlandish way, even though some friends thought it meant we had two birthdays a year. No, it really meant that we celebrated as a family the day each of us came home or our parents “got us”. Those days are lovingly referred to as our “Gotcha Days” and growing up, it mostly meant getting to pick where to go out to eat for dinner, which to a kid that was a big deal! (See, I’ve been a foodie from the beginning.)

Growing up in Louisville provided many opportunities to learn about Korean culture and have a strong adoptive family network. My mom was a co-founder of a local adoptee group that partnered with the Korean community, Korean churches, and international students attending the University of Louisville. They created events for education and interaction to experience the culture from which adoptees came; from Lunar New Year celebrations with local churches to a week-long summer Culture Camp that exposed adoptees to Korean cooking, clothing, writing, art, music, taekwondo and more. (Winner of a 50 pound bag of rice for a bowing contest over here.)

Having support in the community is critical to adoptive families. Remember my struggle in elementary school? I had the best teacher who allowed me to share bits of Korean culture with my class each day for a week that school year. I wore my hanbok (traditional Korean dress), taught my friends how mothers carried their babies in homemade wraps, and even brought Korean foods and snacks for them to taste-test. Even though I was too old to be a camper for the Culture Camps, as a camp counselor and eventual co-director of the camp, I saw the need for kids to have relationships with other kids like them; those who were often the minority in their communities, but also not fully a part of a culture or community that the color of their skin would suggest they belonged. Oftentimes, adoptees do not know their birth history, including any medical or family history. The minimal pieces of information my parents had regarding my birth parents was that my birth mother saw a commercial for an adoption agency and wanted a “better life for me” that at that time in Korean culture, I would not have been afforded being born to a single, unwed mother. My birth father’s name had been blacked out.

People sometimes ask if I ever looked for my birth parents or wanted to know more about my adoption beyond what was given to my parents. For some adoptees, they may feel a sense of abandonment (especially if they are older when they are adopted), a sense of loss, and/or a feeling of something missing from their lives. However, I never felt that tug or urgency to “find my birth family”. Any desire to know more was strictly from a medical side of things if there was anything I needed to know for my own health or the health of my children. The information that was given to my parents was enough for me. I’ve always wanted to visit Korea, but not for any soul-searching purpose or to find my birth family; really more to see and experience the culture.

**Disclaimer: I’m not saying I am trauma-free. With every adoption (domestic or international, adoption as a baby or an older child, open adoption or closed adoption, from full relinquishment of rights or through foster care), there is trauma and it comes in many shapes and sizes. This would be its own blog topic, so I won’t dive deeper here, but know this is an emotional, psychological, behavioral, and sometimes physical part of adoption that needs to be recognized and addressed.

So as a thirty-something adult with (at the time) two littles of my own, my life was flipped in September 2013. What was put on paper and given to my parents was not the truth and suddenly my adoption story turned into a Lifetime movie. Dillon International was the agency my parents used to complete my adoption process. A social worker from Dillon contacted me to see if I was the Stacey they were looking for to provide information regarding my birth family.

Once proper identity was confirmed, I was given the news that my birth family was looking for me; not just a birth mother as outlined in the paperwork. In addition to this new piece of information, it turns out I am also a twin and I have a younger sister and younger brother. My birth parents were married when I was born and still are today. My paternal grandmother and eldest paternal aunt were the ones to take me from the hospital and place me for adoption. Remember, this was years ago and methods of security in hospitals were quite different than they are today. Whereas most adoptive parents now must stay in their child’s birth city or country for certain periods of time before coming home, I was in an orphanage and foster care until I was put on a plane to America. So when what appeared to be a single mother (my aunt) brought a baby to the adoption agency with her story, why wouldn’t they believe her?

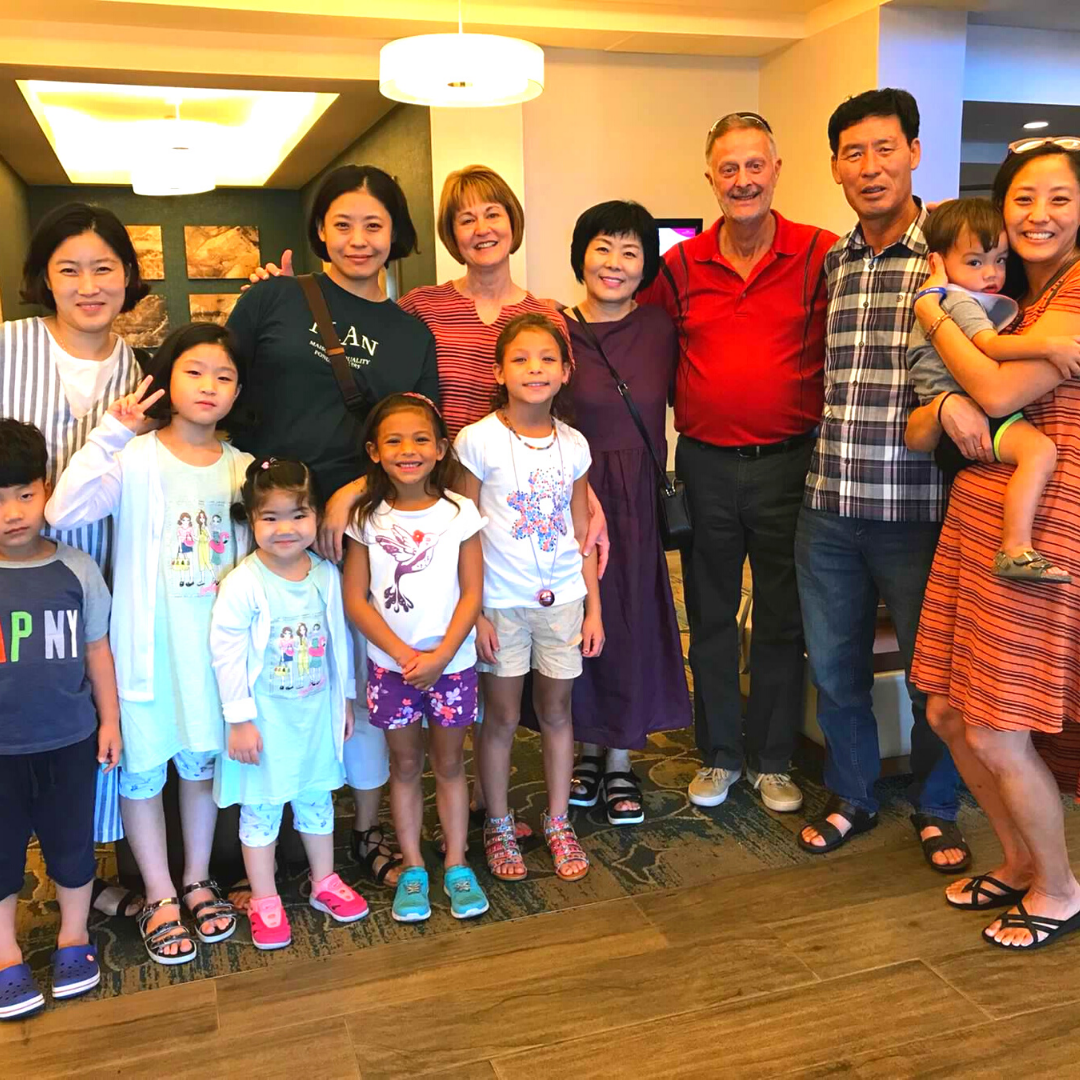

The months following that first contact with Dillon led to letters written and sent for translation both ways between my birth mother and myself. My birth family shared pictures of my siblings growing up and there was definitely no mistaking that I was a twin and related to this family halfway across the world. In each letter from my birth mother, there was an increased urgency to meet me in person. As a mostly private person and very protective of my personal space and family, this was a heavy decision. The staff at Dillon though were amazing in helping sort through what a meeting would entail and what boundaries needed to be in place for my own comfort level. Typically, they try to encourage “reunions” as they call them in the adoptee’s home country; however, with a toddler and nursing baby, working full-time, that really was not an option. Rather we met for the first time in Tulsa, Oklahoma at Dillon International’s HQ.

My parents, my sister, and my nursing one came with me. My birth parents and twin sister came for this first meeting from Korea. To them, it was a reunion. To me, it was a meeting. Semantics drenched in emotions. Dillon International was wonderful in preparing both sides for the meeting; providing cultural references and information to better understand the cross-cultural differences. The visit filled a void for my birth family and for my family, it grew our extended family even more.

Since then, we have been meeting about every two years, once in my hometown for them to see where I grew up and meet more of my family and friends, then another time back in Tulsa where we were asked to speak on a panel of birth families and adoptees to adoptive parents and prospective adoptive parents. Our next meeting was supposed to be this past summer and my family was going to go to Korea for the first time, but with the pandemic that had to be postponed. We still communicate through email, I follow my siblings on Instagram, and we have occasional video chats. In addition to my birth parents and twin sister, I have now met two of my nieces, my younger sister and her oldest son, my brother, and sister-in-law.

There are so many things I could share about being an adoptee; growing up as an adoptee, being married to an adoptee (yes, my husband is a domestic adoptee), being a mother to bi-racial children as an adoptee, being a family that is open to adoption (someday). I definitely feel like my story is what it is to help others, so when it comes to my adoption, I am an open book. Some agencies require adoptive parents to interview an adult adoptee to get her perspective, as part of their rigorous process to bring their child home and I’ve been honored to help friends in this way through the years. If you want to know more about how I was placed for adoption, my experiences with racism and bias, my husband’s adoption story and its differences from mine, how to ask better questions when you see a family made through adoption, how to talk to your kids about adoption and/or their own adoption, I’m here.